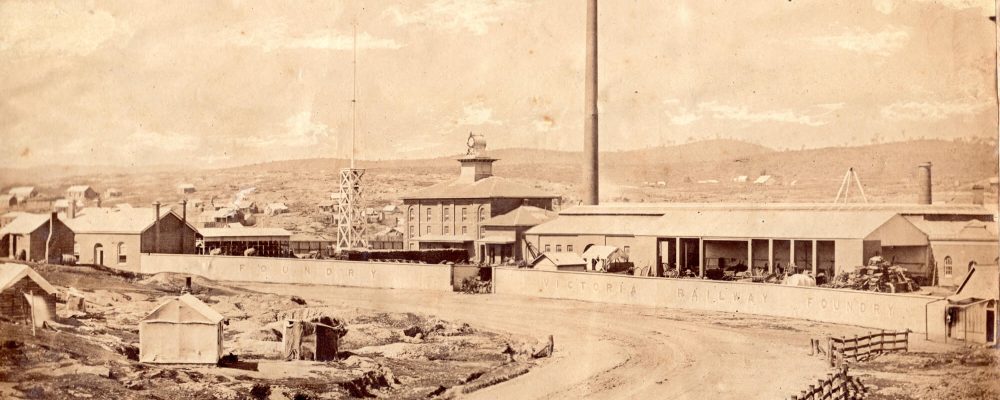

The 20th century brought more change to Castlemaine and its region. While mining was still significant, other industries were established. The Woollen Mill opened in 1875 and lasted till 2013 as Victoria carpets.

Thompson’s foundry, now Flowserve was established a year later than the Woollen Mill. There was a brewery and an abattoir (KR manufacturing) which still operates. Agriculture has become significant with orchards, vineyards and market gardens in the district.

As throughout the world, the World Wars changed society significantly. The horrors of the wars are readily recognised, but particularly WW1 accelerated social change through increased social mobility and population movement. When men are moved halfway around the world and women leave home and farm work for industry, there had to be change. The people of Castlemaine could move to other cities: other people would move to Castlemaine and its district. This was the process which generated the Castlemaine background which so many people will find in their family history.

The late 20thcentury saw some industries succeed, while others faltered. The decline of manufacturing was severe in regional areas but Castlemaine has again reinvented itself. The development of faster trains mean some residents can work effectively in Melbourne while enjoying a tree change. Local tourism has also developed with the development of a café culture and arts community. A Hot Rod ‘street rodding’ community also thrives, filling the streets, especially on weekends with heritage vehicles.

The Castlemaine Art Museum was established by a committee of passionate local people in order to showcase Australian Art. Many notable Australian Artists including Fred McCubbin, Tom Roberts Rupert Bunny and A M E Bale who donated works, grateful for recognition in their own country. Notable among the committee were the Leviny sisters, daughters of Hungarian Silversmith Ernst Leviny who made their home at ‘Buda’ in Castlemaine a house which is open to the public and showcases the work of Leviny and his talented children. The strong Arts tradition has continued in Castlemaine including the biennial State Festival which showcases Arts of all kinds.

Ernst Leviny, a Hungarian silversmith and jeweller, arrived at the diggings in 1853 with expensive but unfortunately inappropriate equipment. He turned his attention successfully back to his business ventures and with his wealth he bought a house, which he renamed Buda. It became the family home and it remained in the family for over a century. With his wealth he was able to encourage his daughters into art and they used the home as a centre for their arts and crafts work.

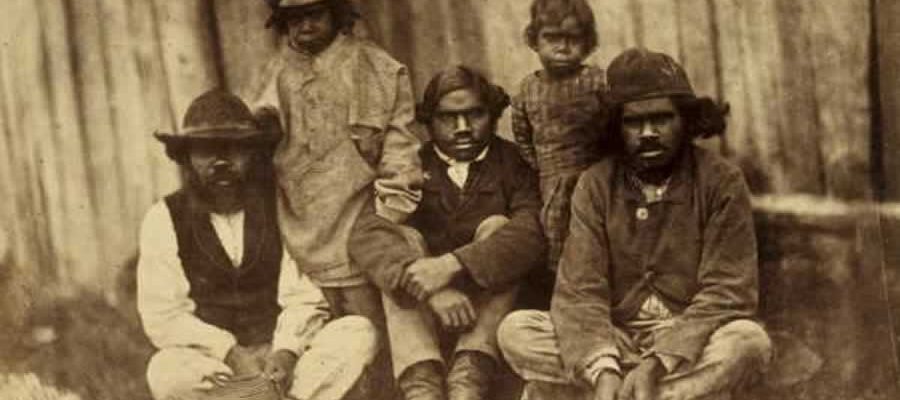

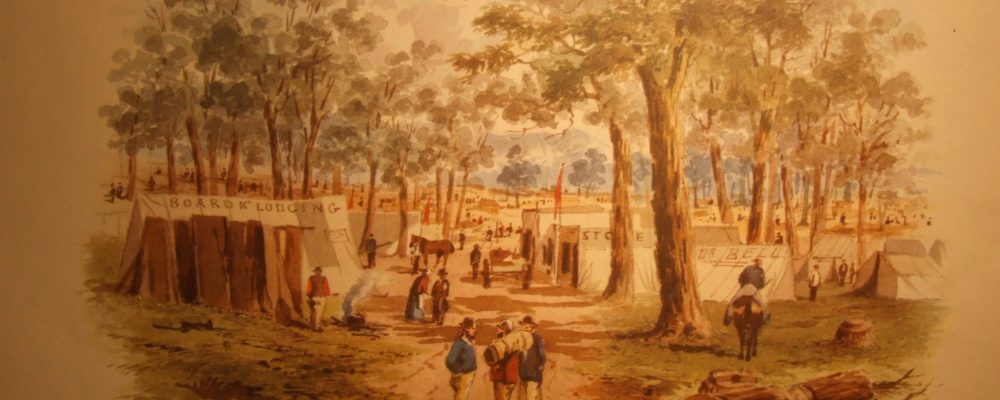

The history of Castlemaine and its district has touched many people in its development from traditional lands, through scattered farming settlements and the surge of the gold discovery. The social movements driving the people to establish a small regional city reflect the wider pressures in Australian society. The changes brought by pastoralists and then gold mining determined the history in the 19th century while the changes brought by industry and social movements (Friendly societies, prohibition and women’s rights) introduced Castlemaine to the 20th century. The world’s next mark on Castlemaine was World War 1. The Australian story is told in microcosm in Castlemaine.